SisterLove is Navigating Its Way and Sharing Lessons with Partners

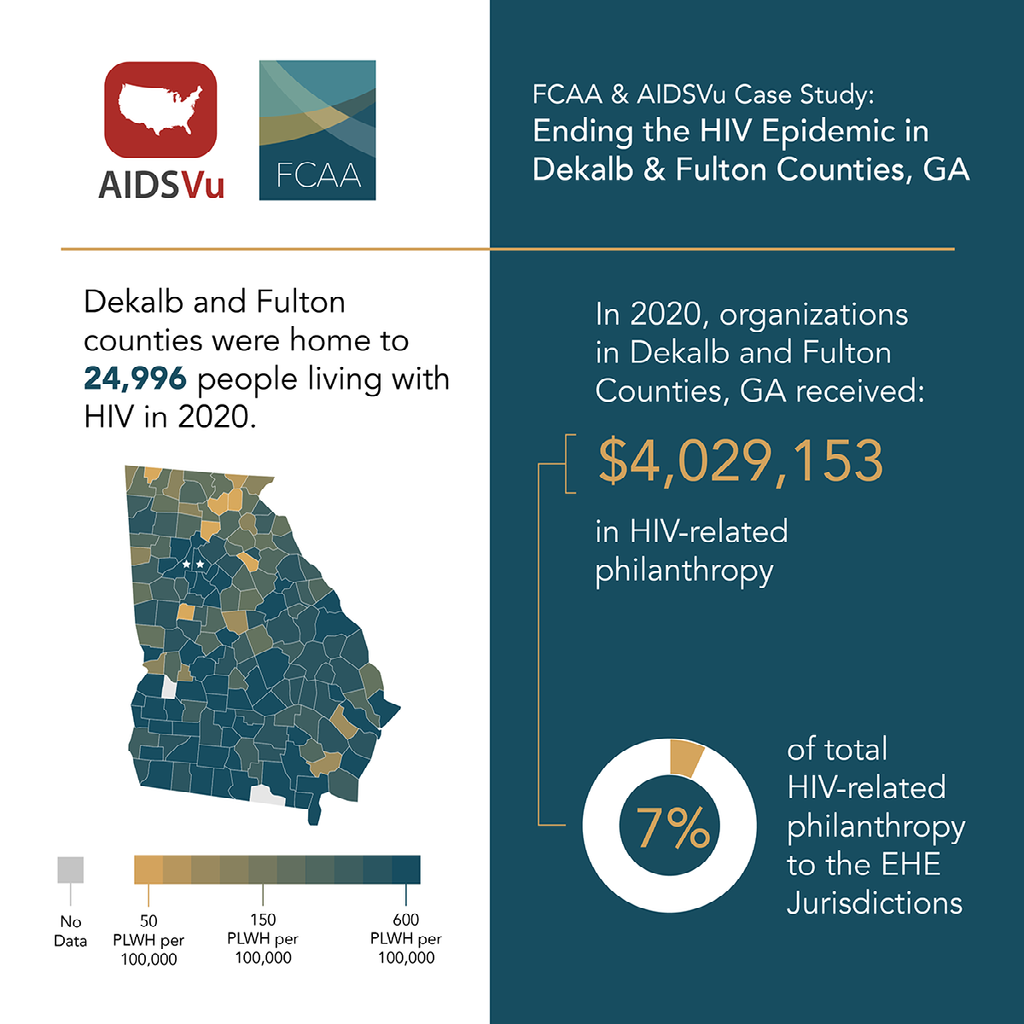

Throughout the past year, FCAA has been delving into the Ending the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. initiative — a ten-year federal program focused on the 57 communities (“jurisdictions”) most affected by HIV. We wanted to assess where and how philanthropic resources are complementing federal funds. As part of this effort, we are highlighting the stories behind the numbers, speaking with individuals and organizations within some of these communities and, through their voices, bringing life to the data.

Our latest interview is with Dázon Dixon Diallo, founder and executive director of SisterLove, Inc. After seeing photos pour in on social media featuring SisterLove’s new “Healthy Love™ Bus,” — a preventive mobile health unit — we wanted to hear more about it. Diallo spoke with journalist Stephen Hicks about this newest program and her hopes for shrinking gaps in care and services in the greater Atlanta area.

Congratulations on the Love Bus. How did it come about?

A sister, Dr. Gaea Daniel of Emory University School of Nursing who has sort of — not secretly, but silently — been following, loving, and supporting SisterLove for years, called us out of the blue. She said she had this grant opportunity from the Direct Relief Fund for Health Equity that she was asked to apply for, and didn’t think of anybody but us; what do we need? We said, “We would love to have a mobile unit.” She wrote the grant gratis, and we got it in January. We purchased the bus in April. It was delivered at the end of September, and we just launched it in December (of 2022).

In the meantime, a lot of things needed to be in place which has taken some time. We’ve had a fantastic team working on this and it’s just really exciting that we’re at this point.

We just had (the mobile unit) loaded up with an audio system, speakers, GPS tracking, all that kind of stuff, because we intend to use it for mobilization, for community education, social events, activities, but also for tracking crisis pregnancy centers or these fake abortion clinics. We want to provide comprehensive bodily autonomy, respectful, gender-affirming, mental health, trauma-informed care that these fake clinics aren’t providing. We’re really excited about being able to integrate all of that and use this health unit as a social change agent.

How has SisterLove adapted to encompass EHE while also focusing on reproductive justice and comprehensive sexual health?

We are not one of the subs or directly funded under the EHE, but we are in Georgia and have funding from the Department of Public Health for our HIV prevention programs. Having said that, it’s been somewhat challenging. The fight for transparency and inclusion (in the EHE program) has been one of our biggest issues. Our health education team has been extremely involved in helping develop some of the local priorities, making sure that there’s inclusion practice, making sure that they were involving women — particularly cisgender Black women, because we tend to be the, “Oh by the way” population.

We’re not solely HIV and sexually transmitted infections; we do a lot of work around Black maternal mortality and reproductive justice work. The intersections of that work kept us pretty active, even during the hard days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a highly affected metro area, I wish I could say I’m keeping hope alive, but there is a long way for us to go. We don’t have state leadership beyond the Ryan White enterprise. You have a lot of the same players for the last 40 years trying to do the same things in the same old way. That’s not as productive when we could take the opportunity through COVID to really fix some stuff and turn it around. But I don’t know if we’ve been able to turn this Titanic fast enough.

When you said that you’re keeping hope alive, how do you do that? What metrics do you use to gauge progress?

I don’t know in terms of a specific number; I gauge progress through a significant increase in the presence and leadership of what I call “E populations.” These are essential populations, those that must not only be included in, but at the forefront of, our thinking, activity, and leadership.

One of the things that keeps me hopeful is that we have many more trans programs led by trans people, women’s programs led by women, HIV positive women’s programs led by Women Living with HIV. We’ve been able to support a lot of that in terms of prevention, education, and educating people living with HIV on the meaningfulness of viral suppression and quality of life-focused types of health management and engagement.

What is philanthropy getting right? Where are the areas for improvement when it comes to adjusting to, adapting to, and centering the needs of Black women and HIV?

One of the things that they’re getting right is that they’re finally seeing us. But what’s wrong is that they are not seeing us with equity yet.

With philanthropy, we oftentimes have a lot more latitude to be innovative and creative; to have less of a pre-described or preset way of engaging and doing our programs and services. We can define that for ourselves based on what we know from the data, from our community’s responses when we’ve asked for what they need and want. We’re able to actually respond to that, which isn’t necessarily the same when you’re dealing with the state health department.

What we need from the donor world is recognizing not only what our situation is and what we’re up against with race, sex, class, and gender identities, but that we also can demonstrate some pretty decent leadership, some pretty cool innovation, and interventions that really work and that are worth investing in.

The voting power that Black women have demonstrated has also raised our visibility to some degree. There has been a shift in recognizing that we already do a lot with less, that we already have a lot of work to do, and so spending most of our time in response to funders’ needs was given a break. Having more general operating support during this time has been great. We have been able to show philanthropy that an investment in our overall work is an investment in everyone’s wellbeing.

Maybe somebody, somewhere is finally getting the message that, when you fix things for Black women, you fix it for everybody.

Are there any suggestions you can give for other service organizations?

I love that we are able to garner more general support based on our own arguments. There might be an RFP (request for proposal) that doesn’t fit us. Or it could fit us, but we would have to do some pretty serious finagling to make that work. We decide not to do it, but (go back to the funder) and say, “Here are the things we are doing and want to do, and if you would like to invest in us, then this is what we need.” And we’ve leveraged that response into funding in a couple of places with Direct Relief and the Healthy Love Bus, for example.

What advice would you give to organizations that are getting started with community engagement? How can they best amplify the voices within community?

First, you have to understand the power and the role of centering. Take a step back and make sure that, at every level, staff is trained up; that they are consistent and excelling at centering the people that matter the most to the organization. That is really critical.

Second is intersectionality. The thing that drives that, inside a reproductive justice framework, is that we actually are rooted in the human rights framework. A lot more organizations could do themselves a favor by learning and understanding that our collective work is actually part of a much larger human rights movement. It’s not only about catching numbers — about getting people tested and knowing their status and getting them into care. It’s making sure that, when they get there, they are treated with equity and dignity. Sometimes we forget that that’s also a part of our work.

Continue to innovate, grow, expand, and go outside their comfort zones. If they’re new, I recommend they partner and incubate. I can’t speak strongly enough of the value that AID Atlanta brought to SisterLove as an incubator for the first couple of years of our existence. That gave us the immediate foundation for what it means to be and operate as an organization. Most non-profits are not started by people who got their master’s degree in non-profit management. We learn by the seat of our pants for the first five years, trying to grow and do the work that we want to do in the community. You can cut that short if you incubate with someone who has already had that experience.

As an organization that’s 33-plus years old, we have positioned ourselves to be the best fiscal sponsor. We incubate others to help organizations that are coming along. Just since the pandemic, we have fiscally sponsored five different organizations — three of which have already gone on to get their 501(c)(3) status. For organizations that have been around a long time, a part of helping to serve your community is supporting new organizations that are also serving your community.

Is there anything else you think FCAA members should know?

It’s important for funders to allow organizations to grow; and invest in that growth in some ways. There are three things (I can point to):

- Non-profit organizations are small businesses with a different IRS designation. Everything you think about how small businesses have to operate — nonprofits have the same issues. Sometimes the difference is how we stay afloat. We aren’t selling products that generate profit. We actually are offering services that require investment. Treating us as small businesses is also really important because that makes us all get in line in terms of our bottom lines, in terms of our planning, in terms of the overall management of our fiscal and financial health. SisterLove owns property on purpose for having those assets, so that we can fall back on something when funding doesn’t come through.

- Allow organizations to think for the future and act in the present. We may not always have the ability to, or interest in, trying to solve an immediate problem that has been going on forever. For example, EHE is a great initiative to achieve something at the federal level. But for all the organizations that need to engage in EHE, there is a future beyond it that they have to be working towards. There are lots of different strategies to get to the end of the epidemic that are complimentary to the EHE plan, but not necessarily congruent with (eg. rights based approaches to care; advocacy for equity, dignity and justice; building solidarity among PLwH; or centering Blackness in the HIV and Reproductive Justice responses).

- Invest in really bold, really different, game-changing ideas. I have found, through some great partnerships, that when I offer up really cool, crazy ideas, they can see it, even though they know it’s not something that’s going to lend itself to a grant report of accomplishments. But I can tell you how far we’ve gotten, what we’re going to do, and that we’re three to five years out from it getting done. If you don’t invest in these ideas, people can’t try them. And if they can’t try them, then they stay stuck in whatever they’re already doing.

And that’s not how we are going to end the epidemic.